We’re all familiar with the headlines by now: “Robots are going to steal our jobs”, “Automation will lead to joblessness”, and “AI will replace human labour”. It seems like more and more people are concerned about the possible impact of advanced technology on employment patterns. Last month, Lawrence Summers worried about it in the Wall Street Journal but thought maybe the government could solve the problem. Soon after, Vivek Wadhwa worried about it in the Washington Post, arguing that there was nothing the government could do. Over on the New York Times, Paul Krugman has been worrying about it for years.

But is this really something we should worry about? To answer that, we need to distinguish two related questions:

The Factual Question: Will advances in technology actually lead to technological unemployment?

The Value Question: Would long-term technological unemployment be a bad thing (for us as individuals, for society etc)?

I think the answer to the value question is a complex one. There are certainly concerns one could have about technological unemployment — particularly its tendency to exacerbate social inequality — but there are also potential boons — freedom from routine drudge work, more leisure time and so on. It would be worth pursuing these issues further. Nevertheless, in this post I want to set the value question to one side. This is because the answer to that question is going to depend on the answer to the factual question: there is no point worrying or celebrating technological unemployment if its never going to happen.

So what I want to do is answer the factual question. More precisely, I want to try to evaluate the arguments for and against the likelihood of technological unemployment. I’ll start by looking at an intuitively appealing, but ultimately naive, argument in favour of technological unemployment. As I’ll point out, many mainstream economists find fault with this argument because they think that one of the assumptions it rests on is false. I'll then outline five reasons for thinking that the mainstream view is wrong. This will leave us with a more robust argument for technological unemployment. I will reach no final conclusion about the merits of that argument. As with all future-oriented debates, I think there is plenty of room for doubt and disagreement. I will, however, suggest that the argument in favour of technological unemployment is a plausible one and that we should definitely think about the possible future to which it points.

My major reference point for all this will be the discussion of technological unemployment in Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s The Second Machine Age. If you are interested in a much longer, and more detailed, assessment of the relevant arguments, might I suggest Mark Walker’s recent article in the Journal of Evolution and Technology?

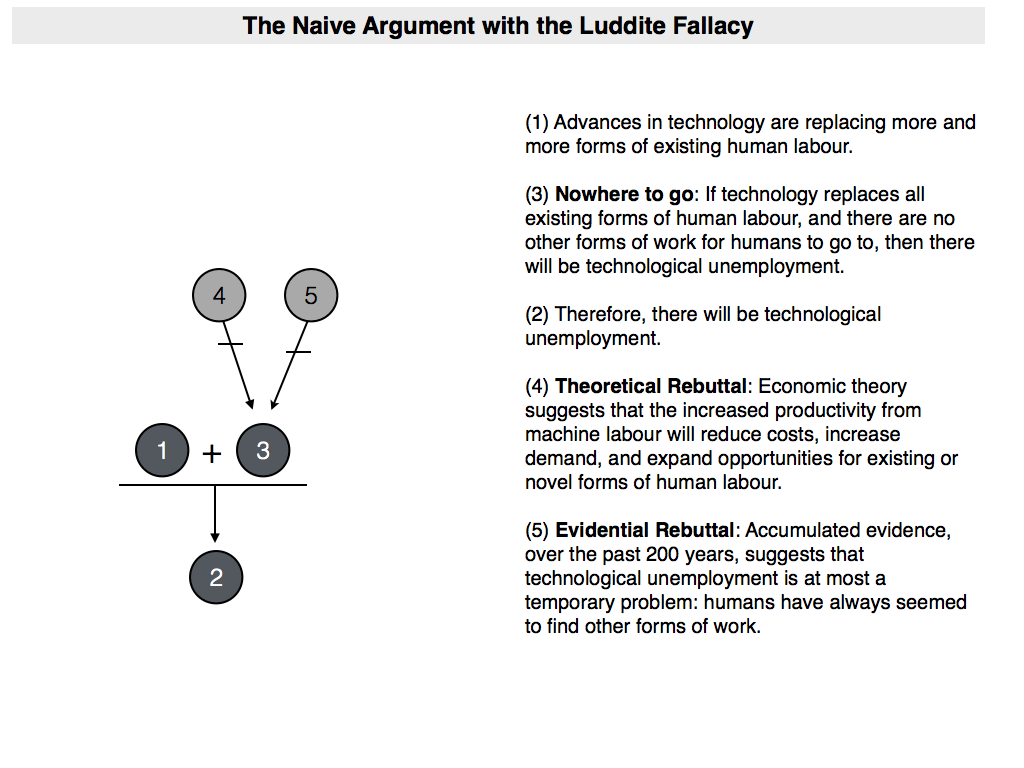

1. The Naive Argument and the Luddite Fallacy

To start off with, we need to get clear about the nature of technological unemployment. In its simplest sense, technological unemployment is just the replacement of human labour by machine “labour” (where the term “machine” is broadly construed and where one can doubt whether we should call what machines do “labour”). This sort of replacement happens all the time, and has happened throughout human history. In many cases, the unemployment that results is temporary: either the workers who are displaced find new forms of work, or, even if those particular workers don’t, the majority of human beings do, over the long term.

Contemporary debates about technological unemployment are not concerned with this temporary form of unemployment; instead, they are concerned with the possibility of technology leading to long-term structural unemployment. This would happen if displaced workers, and future generations of workers, cannot find new forms of employment, even over the long-term. This does not mean that there will be no human workers in the long term; just that there will be a significantly reduced number of them (in percentage terms). Thus, we might go from a world in which there is a 10% unemployment rate, to a world in which there is a 70, 80 or 90% unemployment rate. The arguments I discuss below are about this long-term form of technological unemployment.

So what are those arguments? In many everyday conversations (at least the conversations that I have) the argument in favour of technological unemployment takes an enthymematic form. That is to say, it consists of one factual/predictive premise and a conclusion. Here’s my attempt to formulate it:

(1) Advances in technology are replacing more and more forms of existing human labour.

(2) Therefore, there will be technological unemployment.

The problem with this argument is that it is formally invalid. This is the case with all enthymemes. We are not entitled to draw that conclusion from that premise alone. Still, formal invalidity will not always stop someone from accepting an argument. The argument might seem intuitively appealing because it relies on a suppressed or implied premise that people find compelling. We’ll talk about that suppressed premise in a moment, and why many economists doubt it. Before we do that though, it’s worth briefly outlining the case for premise (1).

That case rests on several different strands of evidence. The first is just a list of enumerative examples, i.e. cases in which technological advances are replacing existing forms of human labour. You could probably compile a list of such examples yourself. Obviously, many forms of manufacturing and agricultural labour have already been replaced by machines. This is why we no longer rely on humans to build cars, plough fields and milk cows (there are still humans involved in those processes, to be sure, but their numbers are massively diminished when compared with the past). Indeed, even those forms of agricultural and manufacturing labour that have remained resistant to technological displacement — e.g. fruit pickers — may soon topple. There are other examples too: machines are now replacing huge numbers of service sector jobs, from supermarket checkout workers and bank tellers, to tax consultants and lawyers; advances in robotic driving seem likely to displace truckers and taxi drivers in the not-too-distant future; doctors may soon see diagnostics outsourced to algorithms; and the list goes on and on.

In addition to these examples of displacement, there are trends in the economic data that are also suggestive of displacement. Brynjolfsson and McAfee outline some of this in chapter 9 of their book. One example is the fact that recent data suggests that in the US and elsewhere, capital’s share of national income has been going up while labour’s share has been going down. In other words, even though productivity is up overall, human workers are taking a reduced share of those productivity gains. More is going to capital, and technology is one of the main drivers of this shift (since technology is a form of capital). Another piece of evidence comes from the fact that since the 1990s recessions have, as per usual, been followed by recoveries, but these recoveries have tended not to significantly increase overall levels of employment. This means that productivity gains are not matched by employment gains. Why is this happening? Again, the suggestion is that businesses find that technology can replace some of the human labour they relied on prior to the recession. There is consequently no need to rehire workers to spur the recovery. This seems to be especially true of the post-2008 recovery.

So premise (1) looks to be solid. What about the suppressed premise? First, here’s my suggestion for what that suppressed premise looks like:

(3) Nowhere to go: If technology replaces all existing forms of human labour, and there are no other forms of work for humans to go to, then there will be technological unemployment.

This plugs the logical gap in the initial argument. But it does so at a cost. The cost is that many economists think that the “nowhere to go” claim is false. Indeed, they even have a name for it. They call it the “Luddite fallacy”, inspired in that choice of name by the Luddites, who protested against the automation of textile work during the Industrial Revolution. History seems to suggest that the Luddite concerns about unemployment were misplaced. Automation has not, in fact, led to increased long-term unemployment. Instead, human labour has found new uses. What’s more, there appear to be sound economic reasons for this, grounded in basic economic theory. The reason why machines replace humans is that they increase productivity at a reduced cost. In other words, you can get more for less if you replace a human worker with a machine. This in turn reduces the costs of economic outputs on the open market. When costs go down, demand goes up. This increase in demand should spur the need or desire for more human workers, either to complement the machines in existing industries, or to assist entrepreneurial endeavours in new markets.

So embedded in the economists’ notion of the Luddite Fallacy are two rebuttals to the suppressed premise:

(4) Theoretical Rebuttal: Economic theory suggests that the increased productivity from machine labour will reduce costs, increase demand, and expand opportunities for existing or novel forms of human labour.

(5) Evidential Rebuttal: Accumulated evidence, over the past 200 years, suggests that technological unemployment is at most a temporary problem: humans have always seemed to find other forms of work.

Are these rebuttals any good? There are five reasons for thinking they aren’t.

2. Five Reasons to Question the Luddite Fallacy

The five reasons are drawn from Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s book. I will refer to them as “problems” for the mainstream approach. The first is as follows:

(6) The Inelastic Demand Problem: The theoretical rebuttal assumes that demand for outputs will be elastic (i.e. that reductions in price will lead to increases in demand), but this may not be true. It may not be true for particular products and services, and it may not be true for entire industries. Historical evidence seems to bear out this point.

Let’s go through this in a little more detail. The elasticity of demand is a measure of how sensitive demand is to changes in price. The higher the elasticity, the higher the the sensitivity; the lower the elasticity, the lower the sensitivity. If a particular good or service has a demand elasticity of one, then for every 1% reduction in price, there will be a corresponding 1% increase in demand for that good or service. Demand is inelastic when it is relatively insensitive to changes in price. In other words, consumers tend to demand about the same over time (elasticity of zero).

The claim made by proponents of the Luddite fallacy is that the demand elasticity for human labour, in the overall economy, is around one, over the long haul. But as McAfee and Brynjolfsson point out, that isn’t true in all cases. There are particular products for which there is pretty inelastic demand. They cite artificial lighting as an example: there is only so much artificial lighting that people need. Increased productivity gains in the manufacture of artificial lighting don’t result in increased demand. Similarly, there are entire industries in which the demand elasticity for labour is pretty low. Again, they cite manufacturing and agriculture as examples of this: the productivity gains from technology in these industries do not lead to increased demand for human workers in those industries.

Of course, lovers of the Luddite fallacy will respond to this by arguing that it doesn’t matter if the demand for particular goods or services, or even particular industries, is inelastic. What matters is whether human ingenuity and creativity can find new markets, i.e. new outlets for human labour. They argue that it can, and, more pointedly, that it always has. The next two arguments against the Luddite fallacy give reason to doubt this too.

(7) The Outpacing Problem: The theoretical rebuttal assumes that the rate of technological improvement will not outpace the rate at which humans can retrain, upskill or create new job opportunities. But this is dubious. It is possible that the rate of technological development will outpace these human abilities.

I think this argument speaks for itself. For what it’s worth, when JM Keynes first coined the term “technological unemployment”, it was this outpacing problem that he had in mind. If machines displace human workers in one industry (e.g. manufacturing) but there are still jobs in other industries (e.g. computer programming), then it is theoretically possible for those workers (or future generations of workers) to train themselves to find jobs in those other industries. This would solve the temporary problem of automation. But this assumes that humans will have the time to develop those skills. In the computer age, we have witnessed exponential improvements in technology. It is possible that these exponential improvements will continue, and will mean that humans cannot redeploy their labour fast enough. Thus, I could encourage my children to train to become software engineers, but by the time they developed those skills, machines might be better software engineers than most humans.

The third problem is perhaps the most significant:

(8) The Inequality Problem: The technological infrastructure we have already created means that less human labour is needed to capture certain markets (even new ones). Thus, even if people do create new markets for new products and services, it won’t translate into increased levels of employment.

This one takes a little bit of explanation. There are two key trends in contemporary economics. First is the fact that an increasing number of goods and services are being digitised (with the advent of 3D printing, this now include physical goods). Digitization allows for those goods and services to be replicated at near zero marginal cost (since it costs relatively little for a digital copy to be made). If I record a song, I can have it online in an instant, and millions of digital copies can be made in a matter of hours. The initial recording and production may cost me a little bit, but the marginal cost of producing more copies is virtually zero. A second key trend in contemporary economics is the existence of globalised networks for the distribution of goods and services. This is obviously true of digital goods and services, which can be distributed via the internet. But it is also true of non-digital goods, which can rely on vastly improved transport networks for near-global distribution.

These two trends have led to more and more “winner takes all” markets. In other words, markets in which being the second (or third or fourth…) best provider of a good or service is not enough: all the income tends to flow to one participant. Consider services like Facebook, Youtube, Google and Amazon. They dominate particular markets thanks to globalised networks and cheap marginal costs. Why go to the local bookseller when you have the best and cheapest bookstore in the world at your fingertips?

The fact that the existing infrastructure makes winner takes all markets more common has pretty devastating implications for long-term employment. If it takes less labour input to capture an entire market — even a new one — then new markets won’t translate into increased levels of employment. There are some good recent examples of this. Instagram and WhatsApp have managed to capture near-global markets for photo-sharing and free messaging, but with relatively few employees. (Note: there is some hyperbole in this, but the point still holds. Even if the best service provider doesn’t capture the entire market, there is still less opportunity for less-good providers to capture a viable share of the market. This still reduces likely employment opportunities.)

The fourth problem with the Luddite fallacy has to do with its reliance on historical data:

(9) The Historical Data Problem: Proponents of the Luddite fallacy may be making unwarranted inferences from the historical data. It may be that, historically, technological improvements were always matched by corresponding improvements in the human ability to retrain and find new markets. But that’s because we were looking at the relative linear portion of an exponential growth curve. As we now enter a period of rapid growth, things may be different.

In essence, this is just a repeat of the point made earlier about the outpacing problem. The only difference is that this time it is specifically targetted at the use of historical data to support inferences about the future. That said, Brynjolfsson and McAfee do suggest that recent data support this argument. As mentioned earlier, since the 1990s job growth has “decoupled” from productivity: the number of jobs being created is not matching the productivity gains. This may be the first sign that we have entered the period of rapid technological advance.

The fifth and final problem is essentially just a thought experiment:

(10) The Android Problem: Suppose androids could be created. These androids could do everything humans could do, only more efficiently (no illness, no boredom, no sleep) and at a reduced cost. In such a world, every rational economic actor would replace human labour with android labour. This would lead to technological unemployment.

The reason why this thought experiment is relevant here is that there doesn’t seem to be anything unfeasible about the creation of androids: it could happen that we create such entities. If so, there is reason to think technological unemployment will happen. What’s more, this could arise even if the androids are not perfect facsimiles of human beings. It could be that there are one or two skills that the androids can’t compete with humans on. Even still, this will lead to a problem because it will mean that more and more humans will be competing for jobs that involve those one or two skills.

3. Conclusion

So there you have it: an argument for technological unemployment. At first, it was naively stated, but when defended from criticism, it looks more robust. It is indeed wrong to assume that the mere replacement of existing forms of human labour by machines will lead to technological unemployment, but if the technology driving that replacement is advancing at a rapid rate; if it is built on a technological infrastructure that allows for “winner takes all” markets; and if ultimately it could lead to the development of human-like androids, then there is indeed reason to think that technological unemployment could happen. Since this will lead to a significant restructuring of human society, we should think seriously about its implications.

At least, that’s how I see it right now. But perhaps I am wrong? There are a number of hedges in the argument — we’re predicting the future after all. Maybe technology will not outpace human ingenuity? Maybe we will always create new job opportunities? Maybe these forces will grind capitalism to a halt? What do you think?

No comments:

Post a Comment